Wayfinding: How space flight affects astronauts' brains

The Canadian Wayfinding experiment aims to discover how astronauts get their bearings and find their way around by looking at their brains while they perform spatial orientation tasks.

Background

In order to create an accurate mental map of its position and surroundings, the brain processes visual, self-sensing, and vestibular (inner ear) information.

Living in a weightless environment like the International Space Station (ISS) challenges an astronaut's internal orientation system. In microgravity, the brain cannot rely on the same signals to map out the location of important features like space modules or emergency escape hatches. Astronauts' orientation and navigation challenges can also affect their ability to perform complex operations in space, like robotics tasks.

Wayfinding's results will teach us more about structural and functional changes that the brain undergoes when working in these tricky conditions. This will help astronauts better prepare for and recover from space missions.

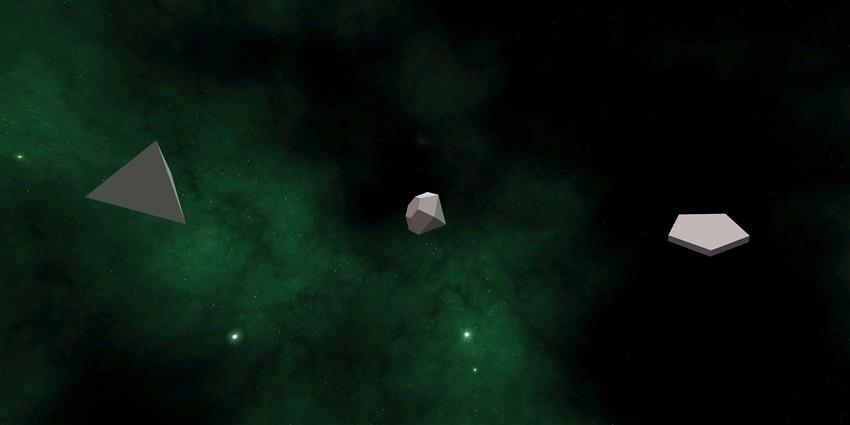

The Wayfinding experiment: Studying how spaceflight affects astronauts' brains. (Credits: Canadian Space Agency, NASA)

Objectives

Wayfinding's main goals are to:

- measure the changes in orientation skills brought on by microgravity aboard the ISS

- look for modifications in brain pathways involved in orientation tasks, like getting from one place to another

- observe how the brain re-adapts upon an astronaut's return to Earth

Impacts on Earth

Orientation relies in part on the correct working of the vestibular system in the inner ear. This experiment will improve our knowledge of medical conditions affecting movement, posture and spatial orientation skills.

Its findings could be beneficial for patients on Earth who suffer from balance disorders like Ménière's disease, which causes severe dizziness, and help shed light on neural degeneration related to aging, which is known to impact the ability to orient in new surroundings.

How it works

Eighteen astronauts are participating in this experiment. They undergo three testing sessions, with the first one occurring six months before departure. Each session has three parts:

- A behavioural assessment, administered on a computer, evaluates the ability to navigate by using different orientation strategies such as tracking the position of “landmarks,” or retracing one's steps to return to a starting location.

- A neuroimaging session uses medical imaging to record brain structures and activity while the astronaut performs spatial orientation tasks.

- A neuropsychological assessment measures different functions that are important for spatial orientation such as attention, perception, and memory skills.

Astronauts complete this sequence again two weeks after their return to Earth and six months later. By comparing the data, researchers can link differences in brain structure and function to changes in orientation skills.

Some people become sick while riding in a car, plane, or boat. Astronauts can experience space adaptation syndrome, a type of motion sickness with symptoms ranging from mild nausea and dizziness to vomiting. Many astronauts wear anti-nausea patches on their skin to prevent these effects during launch and return.

The brightly coloured spots on this MRI (or magnetic resonance imaging) indicate the subject's brain activity as they perform spatial orientation tasks. The part of the brain that lights up depends on the particular task the subject is performing. The Wayfinding team compares similar images obtained from the participating astronauts before and after their flights to identify changes in the brain functioning. (Credit: NeuroLab)

Results

To date, the Wayfinding experiment has found that after a spaceflight, astronauts' brains showed less activity in regions responsible for spatial processing. This suggests that astronauts use different ways of thinking to perform some spatial tasks to adapt to spaceflight.

Timeline

The Wayfinding team began collecting data in October 2017, and the experiment is expected to conclude in 2026.

Research team

Principal investigator

- Dr. Giuseppe Iaria, University of Calgary

Co-investigators

- Dr. Ford Burles, University of Calgary

- Dr. Simon Duchesne, Université Laval